ບຣິດທິກ ຣາຊ

ບຣິດທິກ ຣາຊ (ຈາກ Hindustani rāj, 'ການປົກຄອງ', 'ການປົກຄອງ' ຫຼື 'ລັດຖະບານ') ແມ່ນການປົກຄອງຂອງ ມົງກຸດ ອັງກິດໃນ ອະນຸພາກພື້ນອິນເດຍ, ແກ່ຍາວຈາກ 1858 ຫາ 1947. ມັນຖືກເອີ້ນວ່າ ການປົກຄອງມົງກຸດໃນປະເທດອິນເດຍ, ຫຼື ການປົກຄອງໂດຍກົງໃນປະເທດອິນເດຍ. ພາກພື້ນທີ່ຢູ່ພາຍໃຕ້ການຄວບຄຸມຂອງອັງກິດແມ່ນໂດຍທົ່ວໄປເອີ້ນວ່າ ອິນເດຍ ໃນການນໍາໃຊ້ໃນປະຈຸບັນແລະປະກອບມີເຂດທີ່ປົກຄອງໂດຍກົງໂດຍ ສະຫະລາຊະອານາຈັກ, ເຊິ່ງລວມກັນເອີ້ນວ່າ ອັງກິດອິນເດຍ, ແລະເຂດທີ່ປົກຄອງໂດຍຜູ້ປົກຄອງພື້ນເມືອງ, ແຕ່ພາຍໃຕ້ ການປົກຄອງ ຂອງອັງກິດ, ເອີ້ນວ່າ ລັດ princely . ພາກພື້ນນີ້ບາງຄັ້ງເອີ້ນວ່າ Empire ອິນເດຍ, ເຖິງແມ່ນວ່າບໍ່ແມ່ນຢ່າງເປັນທາງການ.[10] ພື້ນທີ່ຂອງອັງກິດອິນເດຍປະກອບດ້ວຍຫຼາຍລັດໃນປະຈຸບັນຂອງ ປາກີສະຖານ, ອິນເດຍ, ບັງກະລາເທດ, ແລະ ມຽນມາ (ມຽນມາ).

ອິນເດຍ | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1858–1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

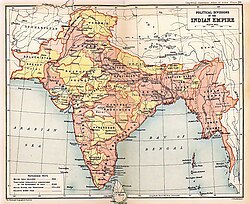

Political subdivisions of the British Raj in 1909. British India is shown in two shades of pink; Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Princely states are shown in yellow. | |||||||||||||||||||||

ບຣິດທິກ ຣາຊ ກ່ຽວກັບຈັກກະພັດອັງກິດໃນປີ 1909 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ສະຖານະ | Imperial political structure (comprising British India[lower-alpha 1] and the Princely States[lower-alpha 2][1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ເມືອງຫຼວງ |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ພາສາລັດຖະການ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ເດມະນິມ | Indians, British Indians | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ການປົກຄອງ | Crown colony | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Queen/Queen-Empress/King-Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1858–1876 (Queen); 1876–1901 (Queen-Empress) | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1901–1910 | Edward VII | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1910–1936 | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1936 | Edward VIII | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1936–1947 (last) | George VI | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1858–1862 (first) | Charles Canning | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1947 (last) | Louis Mountbatten | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1858–1859 (first) | Edward Stanley | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1947 (last) | William Hare | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ສະພານິຕິບັນຍັດ | Imperial Legislative Council | ||||||||||||||||||||

• ສະພາສູງ | Council of State | ||||||||||||||||||||

• ສະພາລຸ່ມ | Central Legislative Assembly | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ປະຫວັດສາດ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 May 1857 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 August 1858 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 July 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| took effect Midnight, 14–15 August 1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ພື້ນທີ່ | |||||||||||||||||||||

• ລວມ | 4,993,650 ຕາລາງກິໂລແມັດ (1,928,060 ຕາລາງໄມລ໌) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ສະກຸນເງິນ | Indian rupee | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

ອ້າງອີງ

ດັດແກ້- ↑ a quasi-federation of presidencies and provinces directly governed by the British Crown through the Viceroy and Governor-General of India

- ↑ governed by Indian rulers, under the suzerainty of The British Crown exercised through the Viceroy of India)

- ↑ Simla was the summer capital of the Government of British India, not of the British Raj, i.e. the British Indian Empire, which included the Princely States.[3]

- ↑ The proclamation for New Delhi to be the capital was made in 1911, but the city was inaugurated as the capital of the Raj in February 1931.

- ↑ English was the language of the courts and government.

- ↑ Urdu was also given official status in large parts of northern India, as were vernaculars elsewhere.[4][5][6][7][8]ແມ່ແບບ:Pn[9]

- ↑ Outside northern India, the local vernaculars were used as official language in the lower courts and in government offices.[8]

- ↑ Interpretation Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 63), s. 18.

- ↑ "Calcutta (Kalikata)", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. IX, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, archived from the original on 24 May 2022, retrieved 24 May 2022,

—Capital of the Indian Empire, situated in 22° 34' N and 88° 22' E, on the east or left bank of the Hooghly river, within the Twenty-four Parganas District, Bengal

- ↑ "Simla Town", The Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. XXII, Published under the Authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1908, p. 260, archived from the original on 24 May 2022, retrieved 24 May 2022,

—Head-quarters of Simla District, Punjab, and the summer capital of the Government of India, situated on a transverse spur of the Central Himālayan system system, in 31° 6' N and 77° 10' E, at a mean elevation above sea-level of 7,084 feet.

- ↑ Lelyveld, David (1993). "Colonial Knowledge and the Fate of Hindustani". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4): 665–682. doi:10.1017/S0010417500018661. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179178. S2CID 144180838. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

The earlier grammars and dictionaries made it possible for the British government to replace Persian with vernacular languages at the lower levels of the judicial and revenue administration in 1837, that is, to standardize and index terminology for official use and provide for its translation to the language of the ultimate ruling authority, English. For such purposes, Hindustani was equated with Urdu, as opposed to any geographically defined dialect of Hindi and was given official status through large parts of north India. Written in the Persian script with a largely Persian and, via Persian, an Arabic vocabulary, Urdu stood at the shortest distance from the previous situation and was easily attainable by the same personnel. In the wake of this official transformation, the British government began to make its first significant efforts on behalf of vernacular education.

- ↑ Dalby, Andrew (2004) [1998]. "Hindi". A Dictionary of Languages: The definitive reference to more than 400 languages. A & C Black Publishers. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7136-7841-3.

In the government of northern India Persian ruled. Under the British Raj, Persian eventually declined, but, the administration remaining largely Muslim, the role of Persian was taken not by Hindi but by Urdu, known to the British as Hindustani. It was only as the Hindu majority in India began to assert itself that Hindi came into its own.

- ↑ Vejdani, Farzin (2015), Making History in Iran: Education, Nationalism, and Print Culture, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-8047-9153-3,

Although the official languages of administration in India shifted from Persian to English and Urdu in 1837, Persian continued to be taught and read there through the early twentieth century.

- ↑ Everaert, Christine (2010), Tracing the Boundaries between Hindi and Urdu, Leiden and Boston: BRILL, pp. 253–254, ISBN 978-90-04-17731-4,

It was only in 1837 that Persian lost its position as official language of India to Urdu and to English in the higher levels of administration.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dhir, Krishna S. (2022). The Wonder That Is Urdu. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-4301-1.

The British used the Urdu language to effect a shift from the prior emphasis on the Persian language. In 1837, the British East India Company adopted Urdu in place of Persian as the co-official language in India, along with English. In the law courts in Bengal and the North-West Provinces and Oudh (modern day Uttar Pradesh) a highly technical form of Urdu was used in the Nastaliq script, by both Muslims and Hindus. The same was the case in the government offices. In the various other regions of India, local vernaculars were used as official language in the lower courts and in government offices. ... In certain parts South Asia, Urdu was written in several scripts. Kaithi was a popular script used for both Urdu and Hindi. By 1880, Kaithi was used as court language in Bihar. However, in 1881, Hindi in Devanagari script replaced Urdu in the Nastaliq script in Bihar. In Panjab, Urdu was written in Nastaliq, Devanagari, Kaithi, and Gurumukhi.

In April 1900, the colonial government of the North-West Provinces and Oudh granted equal official status to both, Devanagari and Nastaliq scripts. However, Nastaliq remained the dominant script. During the 1920s, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi deplored the controversy and the evolving divergence between Urdu and Hindi, exhorting the remerging of the two languages as Hindustani. However, Urdu continued to draw from Persian, Arabic, and Chagtai, while Hindi did the same from Sanskrit. Eventually, the controversy resulted in the loss of the official status of the Urdu language. - ↑ Bayly, C. A. (1988). Indian Society and the making of the British Empire. New Cambridge History of India series. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-521-25092-7.

The use of Persian was abolished in official correspondence (1835); the government's weight was thrown behind English-medium education and Thomas Babington Macaulay's Codes of Criminal and Civil Procedure (drafted 1841–2, but not completed until the 1860s) sought to impose a rational, Western legal system on the amalgam of Muslim, Hindu and English law which had been haphazardly administered in British courts. The fruits of the Bentinck era were significant. But they were only of general importance in so far as they went with the grain of social changes which were already gathering pace in India. The Bombay and Calcutta intelligentsia were taking to English education well before the Education Minute of 1836. Flowery Persian was already giving way in north India to the fluid and demotic Urdu. As for changes in the legal system, they were only implemented after the Rebellion of 1857 when communications improved and more substantial sums of money were made available for education.

- ↑ Britain's Oceanic Empire: Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds, C. 1550–1850 Quote: "British India, meanwhile, was itself the powerful 'metropolis' of its own colonial empire, 'the Indian empire'."